Recent media reports have highlighted the somewhat complex

and hidden costs associated with health care.

The Four Corners report “Mind the Gap” focused on out-of-pocket expenses

and hidden fees from surgeons. Whilst

the ABC medical report on “Secret Pacemaker Payments Boosting Private Hospital

Coffers” focused on the hidden rebates hospitals receive for using various

medical devices.

Recent media reports have highlighted the somewhat complex

and hidden costs associated with health care.

The Four Corners report “Mind the Gap” focused on out-of-pocket expenses

and hidden fees from surgeons. Whilst

the ABC medical report on “Secret Pacemaker Payments Boosting Private Hospital

Coffers” focused on the hidden rebates hospitals receive for using various

medical devices.The two issues are separate, but very much related. Both point to the lack of transparency of financial interactions between specialists, hospitals and a variety of other stakeholders in the health care market.

The first media report highlighted the issue around

“informed financial consent”. It is

mandatory for all patients receiving care from a specialist in a private

hospital to sign a document stating that they agree to the charges related to

the procedure or care for which they are being admitted. But how “informed” is the financial

consent? At a vulnerable time, how

likely is a patient to shop around to get a better quote. How does a patient tell if cheaper care will

result in the same, better or worse outcome?

Does the specialist or hospital have any responsibility to inform

patients that there are other (possibly cheaper) options available?

The first media report highlighted the issue around

“informed financial consent”. It is

mandatory for all patients receiving care from a specialist in a private

hospital to sign a document stating that they agree to the charges related to

the procedure or care for which they are being admitted. But how “informed” is the financial

consent? At a vulnerable time, how

likely is a patient to shop around to get a better quote. How does a patient tell if cheaper care will

result in the same, better or worse outcome?

Does the specialist or hospital have any responsibility to inform

patients that there are other (possibly cheaper) options available?

The second report highlighted the hidden, often lucrative,

negotiations hospitals make with medical device companies, which potentially

affect the choices offered to patients.

The medical devices industry is a less regulated market than

pharmaceuticals, in this respect, and although there is no proof of patients’

outcomes being adversely affected, it has certainly opened a Pandora’s box of

questions regarding whether or not the most appropriate device is being used

and whether the most appropriate device is available equitably to all patients

across the public and private health care sectors. There is also the suggestion that such

arrangements may breach the Trade Practices Act.

There are also other hidden financial arrangements, which are

yet to surface in the national media, but are sure to be exposed in coming

months. Some of these include benefits, payments

or incentives made by Private Hospitals to specialists and specialists having a

financial interest in the hospital or health-care facility (including same

day-units) that they admit their patients too.

The Health Insurance Act 1973 Section 129AA specifically prohibits

a health practitioner from asking, receiving or obtaining, any property,

benefit or advantage of any kind for themselves or others from a private

hospital. It also prevents a private

hospital from inducing a health practitioner to influence admission to

hospital. This intent of this rule is to

ensure that there are no enticements which “encourage” admission to hospital,

increasing the amount of money health insurers pay in benefits to specialists

or hospitals.

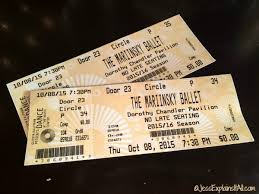

It is unknown how wide-spread the practise of private

hospitals providing incentives to specialists is; however, tickets to shows,

sporting games, dinners, hotel accommodation, reduced fees for clinic room

leases, secretarial services and parking privileges are some of the things

whispered about. It is rumoured, that

some of these are “volume” based. That

is, the more patients a specialist admits to hospital, the more he or she may

benefit. Conversely, should the

admission rate drop, benefits may be reduced.

It is unknown how wide-spread the practise of private

hospitals providing incentives to specialists is; however, tickets to shows,

sporting games, dinners, hotel accommodation, reduced fees for clinic room

leases, secretarial services and parking privileges are some of the things

whispered about. It is rumoured, that

some of these are “volume” based. That

is, the more patients a specialist admits to hospital, the more he or she may

benefit. Conversely, should the

admission rate drop, benefits may be reduced.

Similarly, it is not known what affect a specialist’s

financial interests (such as part-ownership or shares) in a hospital or

health-care facility (including same day-units) may have on their decisions

about whether or not admission is needed, or in fact whether another health

service provider may be a better alternative to hospital for the patient. Such an issue may affect whether or not a

specialist will consider sending a patient to, say a home service provider for

treatment at home, rather than admitting to a hospital or same day-unit that

they have a financial interest in.

As the tangled web of the money trail in health unravels, it

will be interesting to see where this will all lead. More transparency? Real choice? Better outcomes? Lower costs? Hopefully patients will be the winners, as

after all, they are the only reason we all exist.

Julie

Comments

Post a Comment